A PATENT AND AN INVENTION AS A RESULT OF HUMAN CREATIVE WORK

A patent gives its owner a monopoly on a patented product or process. No one other than the patent owner may use the patented invention (either directly or indirectly, or store or offer the patented products). As this is a major economic constraint on competitors and a significant advantage for the patent owner, the law allows granting a patent only for inventions that meet very strict conditions (which have been thoroughly reviewed by patent offices around the world even for many years).

In particular, the patented invention must be new, so that there must be no other source in the world in which the patented invention has been disclosed (for example, an academic study presented somewhere at a conference), and it must be the result of an inventive step. This, in turn, means that it must be innovative, it must be a solution that brings some new innovative solution not apparent at first thought. Such an innovation is often the result of many years of expensive development and has been the motto exclusively of people and their creative work.[1]

The monopoly provided after the grant of the patent then serves as a reward for the patent owner investing in the development and helping to develop human knowledge. At the same time, however, the patent owner must describe the invention and publish it in the patent register, so that this technology is (scientifically) accessible to everyone via the patent registers.

START OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

But times are changing. With the development of artificial intelligence and machine learning tools, even mere algorithms can find approaches and solutions that are innovative and do not even come to experts’ mind at first thought. These algorithms are able to examine dozens of designs, variants and approaches in a second, and evaluate which of the given solutions helps to bring the required innovation, to solve a certain technological problem.

The question then is who should gain the monopoly on this technology. And is such a technology patentable at all? More than one patent office has sought answers to these questions.

The European Patent Office (EPO) thus rejected two patent applications in January because artificial intelligence called DABUS was indicated as the inventor.[2] In both cases, the EPO stated that only a natural person can be the inventor. The regulations simply stipulate that only a human being must be indicated as an inventor and that’s it. [3]

In the United Kingdom, too, an attempt was made to apply for a patent for a technology invented by artificial intelligence (again, it was DABUS), and even in this case, the office rejected the application.[4] Similar attempts were made in the U.S.A., again unsuccessfully.[5] All of these applications rather seem to be an attempt to test how patent offices actually deal with this issue (and not as the real will to obtain a patent).

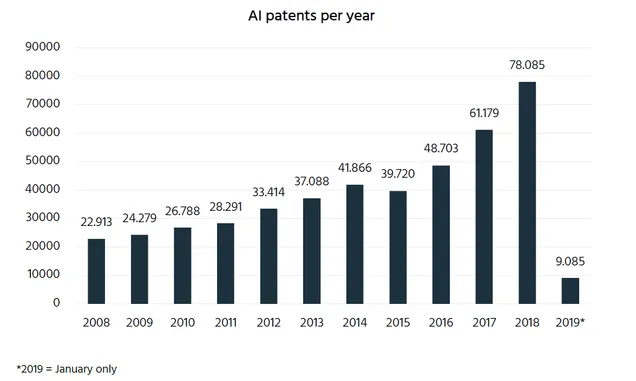

A similar question will return with increasing frequency, as shown in the following graph, showing the exponential growth of patent applications, the subject of which is artificial intelligence itself (which may subsequently engage itself in the “inventive step”):[6]

IMPLICATIONS ON PATENT LAW

Debates are currently taking place before the WIPO, the EPO, but also at the European level. It can also not be ruled out that patent law will cease to exist completely, or at least will practically disappear completely (will become obsolete). Some propose changing the definition of inventor to include inventions created using a machine, modelled after UK copyright law.[7]

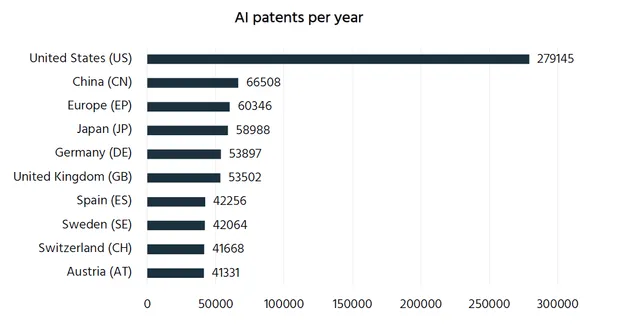

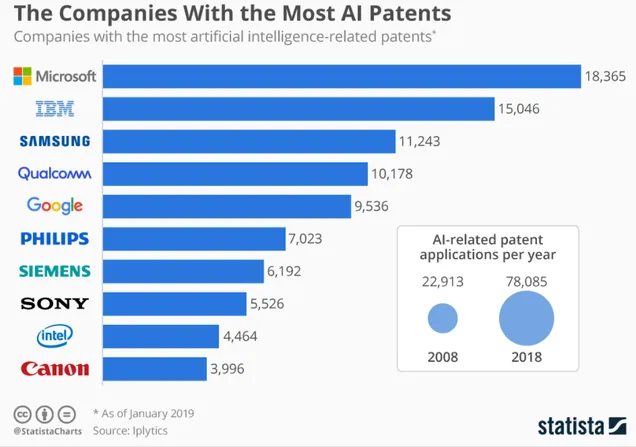

However, with such setting of patent law, there is a risk that it will become the domain of only a few multinational mega-corporations that have sufficient resources to develop and patent artificial intelligence tools (see the chart on owners with the largest number of AI patents / patent applications):[8]

However, there are also opinions on establishing a new category of an intellectual property, something like “AI generated patents”. In any case, the admission of artificial intelligence can also have an overall impact on how patent law works. According to what criteria will an inventive step (innovativeness) be newly assessed? According to what seems innovative to the human inventor or according to what is innovative according to the computer algorithm on which artificial intelligence works?

The whole issue is now escalating, and it is possible that we will see a paradigmatic change not only in patent law, but in the entire body of intellectual property law.