This is the fiftieth anniversary instalment of the information service bringing interesting facts from the world of competition law. This time for October 2024. Again, it is a subjective selection of events that we found interesting.

In our October post, we will introduce two less common types of cartel agreements, namely collective boycotts and non-compete clauses. We will return to prohibited arrangements in distribution agreements, in particular resale price maintenance, and reiterate why it is necessary to cooperate with competition authorities. We will also look at the European Commission's (EC) second attempt to resurrect the Dutch clause in merger control.

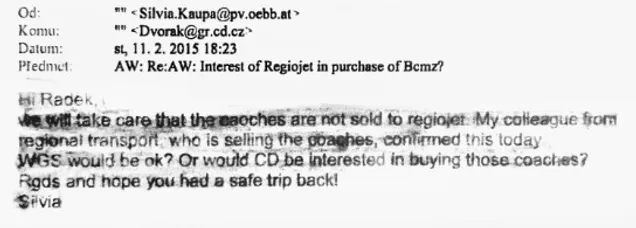

Collective boycott on the railways

The European Commission (EC) has fined Czech Railways (ČD) and its Austrian counterpart (ÖBB) for boycotting RegioJet. The fine for ČD was EUR 31.9 million. The fine for ÖBB was halved to EUR 16.7 million as the Austrian carrier cooperated with the EC during the investigation under the leniency programme. The boycott of RegioJet consisted of an agreement between the national carriers that ÖBB would not sell its scrapped coaches to RegioJet (which was interested), but to ČD or another bidder approved by ČD. Collective boycotts that drive a competitor out of the market or prevent it from entering the market are always prohibited. (In this case, the boycott may also have had a negative impact on reducing carbon emissions, according to the EC.) The EC, however, had no problem proving the aims of the boycott; the e-mail communications between the carriers were quite explicit. RegioJet has already announced that it will seek compensation. Damages are often many times higher than the fines imposed.

Source here[1]

Mergers: non-compete clause – necessary arrangement or cartel?

Non-compete clauses are a common feature of share purchase agreements or other transactions leading to the transfer of a company/business. Their purpose is to protect the acquirer from competitive behaviour by the seller that would reduce the value of the assets being acquired. These clauses are often necessary to complete the transaction and are therefore not prohibited per se. If they are necessary to protect the value of the investment/transaction, competition law allows such clauses to be concluded for a period of two years, or three years if know-how is also transferred in the transaction. In other circumstances, however, competition clauses may constitute a cartel agreement. Particular care should therefore be taken when negotiating competition clauses in transactions.

In October, the Czech Competition Authority ruled on such a clause in the contract for the transfer of Optimum Energy shares between EP ENERGY TRADING (EPET) and VORAGO. VORAGO, as the seller, undertook not to enter into any electricity and/or gas supply contract with any of Optimum Energy’s customers that would result in the termination of those customers’ contractual relationship with Optimum Energy. This clause was to remain in force for a period of five years from the date of approval of the transaction by the Competition Authority (in this case from 25 August 2015), which exceeds the period tolerated by competition law. In the course of the administrative procedure, VORAGO submitted a letter according to which EPET and VORAGO should have agreed in April 2017 that VORAGO was no longer able to guarantee the protection of the customer group and therefore compliance with the clause was no longer necessary. As the record showed that the non-compete clause had been in place for less than two years (and not the agreed five years), the Czech Competition Authority concluded that there was no anticompetitive conduct and dismissed the case.

However, Pharol (formerly Portugal Telecom) was not so lucky, having to pay a fine of EUR 12.15 million because the non-compete clause was clearly not necessary.

Beware: Unreasonably long or incorrectly worded non-compete clauses will often be detected by competition authorities when clearing a transaction as a merger.

Merger: new chances for the Dutch clause

In our last post, we reported on the EC's big loss at the Court in the Illumina/GRAIL merger case and the EC's innovative use of the so-called Dutch clause. Back in September, the EC announced that it would use another option to review problematic deals anyway. In cases where a merger does not meet the notification criteria but the national competition authority has so-called call-in powers, i.e. it can order the merging companies to notify the transaction anyway, the EC can have the case referred to it. There are currently eight such Member States in the EU, with others, including the Czech Republic, set to follow.

In October, the European Commission seized the opportunity and agreed to accept Nvidia's proposed acquisition of startup Run:ai Labs from the Italian Competition Authority. The transaction does not meet the notification criteria either at EU level or in Italy. However, the Italian Competition Authority ordered the merging companies to notify it under its call-in powers and subsequently asked the EC to take over the case. It remains to be seen how the EU courts will assess the situation this time. After all, the situation differs from the Illumina/GRAIL case in that at least one Member State appears to have jurisdiction to review the transaction, even though the notification criteria are not met anywhere.

Anti-competitive distribution agreements

The hiatus in resale price maintenance decisions did not last long. In October, this "popular" anti-competitive arrangement in distribution contracts returned to the competitive arena.

The French Competition Authority has fined two electrical equipment manufacturers, Schneider Electric and Legrand, and their two distributors, Rexel and Sonepar, a total of EUR 470 million for two resale price maintenance agreements. The agreements provided that if an end customer approached the manufacturer and asked for a lower price than that offered by the distributor, the manufacturer would reduce the purchase price paid to the distributor, so that the distributor could offer the end customer the same price as that requested directly from the manufacturer. Although the distributors could have offered the customer an even lower price, the Competition Authority found that they did not do so, again in consultation with the manufacturers. In doing so, they restricted intra-brand competition.

In October, the Romanian Competition Authority fined printer manufacturer OKI Europe RON 3.35 million (approx. EUR 672,459) for, among other things, resale price maintenance. According to the Competition Authority, OKI Europe set different resale prices in different European countries. In order to maintain these prices, it then restricted exports. In Romania, it did so in cooperation with its distributor General Systems, which was not sanctioned because it reported the anti-competitive conduct under the leniency programme.

Distribution agreements were also dealt with by the Polish Competition Authority in October, but it concluded its case with an acceptance of commitments rather than a fine. According to the Competition Authority, computer equipment manufacturer Dell entered into market-sharing agreements with its wholesalers and authorised resellers. These were based on an internal transaction registration system. If a reseller registered a potential transaction with an institutional or business customer in the system, Dell could prohibit other resellers from making a competing offer to that customer. The commitments offered by Dell and accepted by the Polish Competition Authority included the termination of the registration system. The Polish Competition Authority also fined Dell PLN 6 million (approximately EUR 1.38 million) for providing false information during the investigation.

How to (not) abuse a dominant position

The Austrian Competition Court fines Österreichische Post EUR 9.2 million for abusing its dominant position in the addressed mail market. This category includes mailings that are identical in format and weight, contain only advertising and a printed address, and consist of at least 400 individual mailings. According to the Austrian Competition Authority, which proposed the fine, the abuse consisted in granting mail consolidators a limited range of discounts, lower discounts or lower bonuses on annual fees compared to large direct customers for the same annual volume. (A consolidator is a transport company that collects mail from several customers for transport, sorts it at major transport hubs and processes it for final delivery by the postal service, thereby saving costs for the customers. It therefore competes to some extent with the postal service. In addition, it increases the costs for the postal service. At the same time, the Competition Authority took into account the fact that Österreichische Post had entered into confidentiality agreements with large customers regarding the discounts and bonuses it negotiated with them, thereby attempting to conceal the discrimination against consolidators.

The EC fined Teva EUR 462.6 million for abusing its dominant position in the market for multiple sclerosis drugs. The abuse led to delays in the market entry of products competing with its successful drug Copaxone, including in the Czech Republic. Teva achieved this both by artificially prolonging patent protection through abuse of patent rules and procedures and by systematically disseminating misleading information about the safety, efficacy and therapeutic equivalence of competing products (denigration), for example in its communications with doctors.

Denigration or disparagement will be considered an abuse of a dominant market position in the future. As the EC has stated, disparagement includes not only the dissemination of false claims, but also misleading or alarmist messages. It is therefore not only pharmaceutical companies that need to be careful when referring to competing products in external communications and campaigns.

Non-cooperation does not pay

During October, the competition authorities also imposed fines on undertakings for failing to cooperate in investigations into possible anticompetitive conduct.

The Slovak Competition Authority has fined a provider of hosting and domain name services more than EUR 60,000 for failing to provide information requested during an on-site inspection. While investigating the suspected cartel, the Competition Authority found that approximately 500,000 e-mail messages had been deleted from the competitor's mailboxes prior to the start of the inspection. However, these messages are still in the possession of the relevant hosting and domain service provider, which has refused to disclose them. As the Competition Authority considered these e-mails to be key evidence, it imposed a fine close to the maximum level allowed by law. It is important to remember that competition authorities can also require third parties to cooperate and impose fines if they obstruct the investigation in any way, even if they were not involved in the anti-competitive conduct.

The Greek competition authority fined Motor Oil (Hellas), Corinth Refineries EUR 9.2 million for delaying an onsite inspection carried out by EC officials in cooperation with the Greek Competition Authority. Motor Oil also failed to ensure the availability of requested business documents. In addition to Motor Oil, the Greek Competition Authority also fined an individual EUR 50,000.